To read or watch this in English, click here.

이 대화는 현재 한국어로 제공됩니다.

오른쪽 하단의 CC – 자막 -을 클릭 한 다음 설정에서 한국어를 선택하십시오.

아래의 필기 기록을 참고하십시오.

This talk is now available in Korean.

Click CC – Closed Captioning – on the bottom right, then choose Korean in Settings.

Please also see the written transcript below.

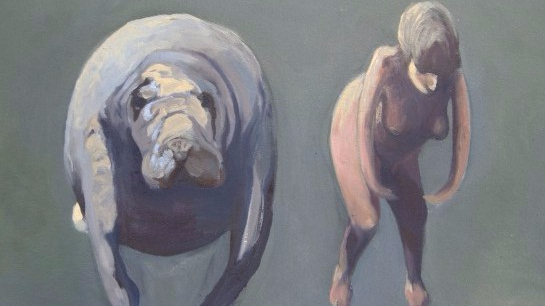

이 그림은 제가 미술 석사 학위 과정을 마치고 일년 후에 그렸는데, 이 그림으로 시작하고 싶었어요. 왜냐하면 제가 장애인권 운동과 장애학, 그리고 동물 윤리의 교차성을 보는 데 있어서 생각을 구성하고 발전하는데 도움을 준 그림이거든요. 이 그림은 장애를 가진 다른 세 동물과 저를 그린 자화상입니다. 필요한 분이 계실지 모르니 간단한 시각 정보를 드릴 게요.

네 개의 형상이 회색 바닥과 흰 벽을 배경으로 서 있거나 누워 있어요. 크고 노란 의학적 화살표가 이 몸들의 비정상적인 부분을 가리키고 있고요. 그들은 일렬로 서 있습니다. 어른 돼지는 서 있고, 검은 송아지가 바닥에 쓰러진 채 누워있고, 제 자화상인 인간은, 벌거벗고 굽은 채로 관객을 응시하고 있어요. 아기 돼지 하나가 마찬가지로 바닥에 웅크린 채 화면 밖을 응시하고 있어요.

간단하게 말하자면, 저는 조사할수록 장애를 가진 몸이 동물 산업의 전반 모든 곳에 존재한다는 것을 알게 되었고, 또한 장애 역사와 저의 장애학 연구의 곳곳에 동물의 몸이 있었다는 것도요. 이 그림을 제가 오늘 할 이야기의 시각적 상징으로써 여기 띄워 두고 싶었어요.

오늘 저는 제가 쓴 글을 읽을 건데, 이 글은 제가 쓴 책의 일부이기도 하고, 최근 칼라 피츠제랄드와 클레어 진 김이 인종, 종, 그리고 성에 대한 글을 모은 아메리칸 계간지의 특별호에 실렸어요. 지금부터 읽기 시작할 텐데, 제가 혹시나 너무 빨리 읽거나 빨리 말한다면 제게 알려주세요.

2010년 9월, 나는 캘리포니아의 Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin County에서 주관하는 행사에 참여하기로 했다. 행사 이름은 The Feral Share였는데, 지역 기반 유기농 농산물 축제이자, 다른 한편으로는 예술 기금 마련 행사이기도 했고, 또 다른 한편으로는 철학적 행사이기도 했다. 나는 바로 마지막, 행사의 철학적 즐거움을 위해 초대받았고, 육식의 윤리에 관해 비건 대표가 되어 토론하기로 예정되어 있었다.

So I wanted to begin with this painting, which I did a year after I graduated from my MFA program. And I wanted to begin with this painting because it really sort of helped form and propels a lot of my work in terms of looking at the intersections between disability activism and disability studies, and animal ethics. This is a painting that is a self-portrait of me with three other animals who also have my disability. So I am going to give a brief visual description of it, in case anyone needs it.

Here is the visual description: Four figures stand or lie on a grey floor with an off-white wall behind them. There are large yellow medical arrows pointing to the abnormal parts of their body. They are in a row. An adult pig stands, a black calf lies collapsed on the floor, a human, a self-portrait, stands nude and bent staring out at the viewer. A piglet lies curled on the floor staring back as well.

Basically, the more I looked the more I found the disabled body is really everywhere in animal industries and I also found that the animal body is everywhere in disability history and in my work in disability studies. I wanted to kind of have this up there to represent some of the things in a visual format that I will be talking about in my presentation.

I am going to read a paper that I wrote that is a section of my book and it recently came out in American Quarterly in a special issue that Carla Fitzgerald and Clair Jean Kim put together on race, species, and sex. So I will just go ahead and start reading, and if I read too quickly or speak too quickly please someone type in and let me know.

In September 2010 I agreed to take part in an art event at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin County, California. The Feral Share, as the event was named, was one part local and organic feast, one part art fund-raising, and one part philosophical exercise. I was invited to be part of the philosophical entertainment for the evening: I was to be the vegan representative in a debate over the ethics of eating meat.

내가 토론할 상대는 환경 변호사, 목장 운영자이자, “정당한 돼지고기: 공장식 축산을 넘어선 삶과 좋은 음식을 찾아 Righteous Porkchop: Finding a Life and Good Food beyond Factory Farms”의 저자인 니콜레트 한 나이먼Nicolette Hahn Niman이었다. 나의 파트너, 데이비드David는 행사에 시간 맞춰 참석했지만, 우리가 접근할 수 없었던 층에서 열렸던 예술 행사에 다른 사람들이 참석할 동안 사십 분 정도를 아래층에서 둘이서만 앉아 있었다. 그 층에는 우리와 저녁 요리를 마무리하는 요리사 몇뿐이었는데, 저녁 요리는 풀을 먹고 자란 쇠고기 아니면 치즈 라비올리였다. 데이비드와 나는 이 행사의 접근성에 대해 사전에 언질을 받았지만, 그곳에 앉아 기다리면서 점점 불편해졌다. 내 안의 장애인권 활동가는 내가 온전히 참여할 수 없는 행사에 참여하기로 동의한 것에 점점 죄책감을 느꼈다. 조용히 휠체어에 앉아 무해하게 기다리던 나는 마치 이 행사와 이 예술 회관에 원천적으로 박혀 있는 차별을 용인하는 것처럼 느껴졌다. 마치 내가 이 행사에 참석하는 것이 “아냐 괜찮아, 나한테 적합한 장소를 제공할 필요 없지, 내 장애는 내 개인적인 투쟁인 걸 뭐”라고 말하고 있는 것처럼.

데이빗과 나의 소외감은 우리의 음식이 나왔을 때 증폭되었다. 행사장에 있는 유일한 비건 두 명으로서, 우리에게는 따로 요리가 제공되었고, 요리는 대부분 구운 채소였다. 그때 나는 한 방을 가득 채운 잡식인들에게, 내가 왜 비건이 됐는지 이유를 설명해야 하는 참이었고, 나는 이 접시의 음식이 어떻게 읽힐지 자각하고 있었다. 다르고 낯선, 다른 음식들만큼 맛이 있지도 않으면서 쓸데없이 더 많은 일거리를 만드는 음식. 나는 그 방에서 완전히 혼자라는 생각을 하며 방으로 들어섰는데, 내가 그곳에서 유일하게 가시적인 장애가 있는 개인이라서 뿐만 아니라, 접시에 동물성 식품이 없는 건 데이비드를 제외하고 나밖에 없었기 때문이다.

마이클 폴란Michael Pollan은 “잡식인의 딜레마The Omnivore’s Dilemma”에서 채식인이 되는 데 가장 문제였던 것은 “미묘하게 소외되는” 것이었다고 한다. 음식에 대해 글을 쓰는 사람들은 종종 자신이 윤리적 가치를 위해 얼마만큼의 사회적 고립감을 마주할 준비가 되어있는지 판단하는데 놀라울 만큼의 에너지를 투자한다. 많은 유명한 잡지나 신문의 기사가 채식인이나 비건이 되면서 겪는 “어려움” 혹은 사회적 낙인- 눈을 굴리거나, 놀리거나, 채식인을 바라보는 시선 등에 관해 이야기 한다. 조나단 사프란 포어Jonathan Safran Foer는 우리가 “음식에 대해서는 특히나, 우리 주변 다른 사람들에게 맞춰 행동하려는 강한 욕구가 있다”고 한다. 이러한 기사들이 채식 경험을 어떻게 주변화하는지는 딱 잘라 말할 수 없다. 개인이 채식하거나 비건이 되기로 했을 때 직면해야 하는 어려운 문제는 많다. 가령, 양질의 신선한 음식을 구할 수 없는 저소득층 지역, 신선한 양질의 음식을 구하기 어려운 음식 사막의 현실, 그리고 그런 지역은 주로 유색 인종이 거주하는 지역이고, 정부는 채소나 과일보다는 고지방 동물성 식품과 식단을 장려하고 보조금을 지급한다.

I was debating Nicolette Hahn Niman, an environmental lawyer, cattle rancher, and author of “Righteous Porkchop: Finding a Life and Good Food Beyond Factory Farms”. My partner, David, and I got to the event on time, but spent the first forty minutes or so sitting by ourselves downstairs while everyone else participated in the art event, which took place on an inaccessible floor of the building. Our only company was a few chefs busily putting the finishing touches on the evening’s meal—a choice of either grass-fed beef or cheese ravioli. David and I had been warned prior to the event about the lack of access, but as we sat there waiting we began to feel increasingly uncomfortable. The disability activist in me felt guilty that I had agreed to partake in an event that I could not participate in fully. My innocuous presence, as I quietly sat downstairs in my wheelchair waiting, somehow made me feel as if I were condoning the discrimination that was built into the event and the art centre itself. As if my presence were saying, “It’s OK, I don’t need to be accommodated—after all, being disabled is my own personal struggle.”

David’s and my alienation was heightened soon after when we were given our meal—as the only two vegans in the room we were made a special dish by the chefs (some of whom were from Alice Waters’s famous Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse). The dish was largely roasted vegetables. As I was about to expound to a room full of omnivores on the reasons for choosing veganism, I felt keenly aware of how this food would be read — as isolating and different, as creating more work for the chefs, and as unfilling in comparison with the other dishes. I entered into the debate with a keen sense of being alone in that room, not only because I was the only visibly disabled individual, but because, besides David, I knew I was the only one with no animal products on my plate.

Michael Pollan writes in “The Omnivore’s Dilemma” that the thing that troubled him the most about being a vegetarian was “the subtle way it alienate(d) me from other people.” People who write about food often spend a surprising amount of energy deciphering how much feeling of social alienation they are willing to face for their ethical beliefs. Countless articles in popular magazines and newspapers on the “challenges” of becoming a vegetarian or vegan focus on the social stigma one will face if they “go veg” — the eye rolling, the teasing comments, the weird looks. Jonathan Safran Foer writes that we “have a strong impulse to do what others around us are doing, especially when it comes to food.” It is difficult to ascertain what role these articles themselves play in marginalizing the vegetarian experience. There are many pressing issues that face individuals who would perhaps otherwise choose to try to become vegetarian or vegan, such as the reality of food deserts in low-income, and often largely people of colour neighbourhoods, and a government that subsidizes and promotes animal-and fat-heavy diets versus ones with vegetables and fruits.

하지만, 대다수 기사는 이러한 심각한 구조적인 문제를 짚기보다는 고기와 동물성 식품을 거부하는 데 있어서 마주하는 어려움을 한 개인의 정상성과 수용 능력 문제로 치부해 버린다. 현대 미국 문화는 동물을 걱정하는 사람을 비정상이라고 그려낸다. 동물권 활동가들은 광적이고, 인간을 혐오하며, 심지어는 테러리스트로까지 묘사된다, 채식인과 비건들은 멍하고, 히스테릭하고, 감성에 도취되어 있거나, 음식에 관해 신경질적인 것으로 비춰진다. 심지어 채식 음식조차 마찬가지로 묘사되는데, 가령 고기 대체 식품은 연구실 혹은 과학 실험으로 묘사된다. 많은 동물 단백질 대체 식품이 전통 미국 음식이 아니므로, 이런 음식을 이상하고 부자연스러운 것으로 재현하는 것은 미국인 정체성(“진짜” 미국인이 먹는 것은 진짜 고기)을 강화하며 타자(타 문화)를 이국적exotic한 것으로 타자화 한다. 하지만, 동물을 먹지 않는 이들의 비정상성을 가장 잘 드러내는 건 다름 아니라 인기 있는 비건 팟캐스트이자 책의 이름 “비건 괴짜Vegan Freak”다. 이 제목은 얼마나 많은 비건이 주류 문화가 자신들을 이렇게 (괴짜Freak) 바라본다고 느끼는지 보여준다.

나는 채식인이나 비건이 되는 데 어려움이 없다고 말하고자 하는 게 아니다. 미디어와 다양한 작가가 비건 혹은 채식인 라이프스타일이라고 깔보듯이 불리는 채식인 및 비건의 삶을 기이하게 보이도록 만드는데 (enfreakment) 일조하고 있다는 것이다. 물론, 동물을 고려하는 사람의 타자화는 새로운 것이 아니다. 다이엔 비어스Diane Beers는 “잔혹함을 방지하기 위하여: 미국의 동물권과 동물권 운동의 역사와 유산For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States”에서 말하길, “몇몇 19세기 후반 의료진은 이러한 이상 행동을 설명하기 위해 진단 가능한 정신 질환을 지어냈다. 그들은, 이 갈 곳을 잃은 영혼들은 슬프게도 ‘주필사이코시스zoophil-psychosis’가 있다고 말했는데” 비어스 왈, 주필사이코시스(동물에 대해 과도하게 우려하는 질환)는 “보다 병에 취약한” 여성이 진단받을 확률이 더 높았다. 영국과 미국의 초기 동물권 운동이 대다수 여성으로 구성되어 있었기 때문에, 이런 비난은 인간 여성과 비인간 동물 모두에 대한 통제를 굳건히 하는 데 이용되었다.

However, rather than focus on these serious structural barriers, many articles often present the challenge of avoiding meat and animal products as a challenge to one’s very own normalcy and acceptability. Those who care about animals are often represented as abnormal in contemporary American culture. Animal activists are represented as overly zealous, as human haters, even as terrorists, while vegetarians and vegans are often presented as spacey, hysterical, sentimental, and neurotic about food. Even vegetarian foods become “freaked,” and alternatives to meats are often described as lab, or science experiments. Since many animal protein alternatives are not traditionally American, the marginalization of these foods as somehow weird or unnatural works both to solidify an American identity (what “real” Americans eat: real meat) and to exoticize the other. However, the abnormality of those who do not eat animals is perhaps best exemplified by the name of a popular vegan podcast and book: “Vegan Freaks”. The title refers to how many vegans feel that they are perceived by mainstream culture.

My point is not to say that there is no challenge to becoming a vegetarian or vegan, but rather to point out that the media, including various authors, contribute to the “enfreakment” of what is so often patronizingly referred to as the vegan or vegetarian “lifestyle.” Of course, the marginalization of those who care about animals is nothing new. Diane Beers writes in her book “For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States”, “that several late nineteenth-century physicians concocted a diagnosable form of mental illness to explain such bizarre behaviour. Sadly, they pronounced, these misguided souls suffered from ‘zoophil-psychosis.’” As Beers describes, zoophil-psychosis (an over concern for animals), was more likely to be used to diagnose women who were understood as “particularly susceptible to the malady.” As the early animal advocacy movement in the UK and the United States was largely made up of women, such charges worked to uphold the subjugation both of women and of nonhuman animals.

역사가 보여주듯이, 그리 멀지 않은 과거에, 나이먼과 나는 이런 주제에 대해 권위를 가지고 이야기하도록 초청받지 못했을 것이다. 우리 둘 다 여성이기에. 하지만 나이먼과 나는 둘 다 백인이기도 하다. 이는 동물 윤리 담론 속에서 인종 차별이 아직도 충분히 다뤄지지 않는다는 것을 보여준다. 비록 역사적으로 중상층 그리고 상류층 여성이 동물권 운동의 대다수를 차지해왔지만, 여성이 지도직을 맡을 수 있게 된 것은 1940년대 후반에 이르러서이다. 유색 인종People of Colour은 지도직은 차치하고서라도 담론에 참여할 기회마저 협소했다. 이러한 가부장제와 인종차별의 역사가 동물 윤리, 지속 가능성, 그리고 식량 정의에 관한 대화에 깊은 영향을 끼친다는 사실은 안타깝게도, 전혀 놀랍지 않다.

뉴욕 타임스가 육식을 정당화 하는 가장 훌륭한 논리를 가리는 대회의 심사 위원을 오롯이 백인 남성 다섯으로만 구성하여 캐럴 제이 아담스Carol J. Adams, 로리 그루엔Lori Gruen, 그리고 에이 브리즈 하퍼A. Breeze Harper가 항의 편지를 쓰게 된 것이 바로 작년이다. 이러한 주제로 학회와 출판 기회, 그리고 미디어의 관심을 받는 이들은 반복적으로 백인 남성이다. 아담스, 그루엔, 그리고 하퍼는 “동물을 먹는 것에 대한 윤리적 논의는 정상적인 것으로 작동해온 성차별과 인종차별로 점철되어 있다”고 말했다.

장애와 장애인 역시 이러한 담론에서 배제됐고, 에이블리즘Ableism(장애인 차별) 역시 정상적이고 자연스러운 것으로 취급됐다. 장애인 공동체는 동물권 공동체와 어려운 관계를 맺어 왔고, 지적 장애가 있는 일부 사람들의 인간성을 부정해도 된다고 이야기한 철학자 피터 싱어Peter Singer의 주장에 관한 토론이 이를 대표적으로 보여준다. 하지만 덜 극단적인 예를 들더라도, 이 운동이 건강과 신체 단련에 가진 집착 때문인지 아니면 교육과 운동 행사에 대한 접근성에 대한 인식 부족 때문인지 장애인 전반과 장애인 개인에게 영향을 끼치는 다양한 문제는 동물 복지와 지속 가능성 운동에서 배제됐다.

As this history suggests, not so very long ago, Niman and I would not have been invited to speak with any sort of authority on these topics because we are women. However, Niman and I are also both white, a fact that reflects the reality that racism is largely still an under-addressed issue within animal-ethics conversations.

Just last year, the scholars Carol J. Adams, Lori Gruen, and A. Breeze Harper were driven to write a letter of complaint to the New York Times for inviting a panel that consisted solely of five white men to judge a contest seeking the best arguments for defending meat-eating. Repeatedly those who are given space at conferences, publication opportunities, and media attention on these topics are white and male. Adams, Gruen, and Harper write, “The fact is that ethical discussions about eating animals are permeated with sexist and racist perspectives that have operated as normative.”

Disability and disabled people have also largely been left out of these conversations, and ableism has similarly been rendered as normative and naturalized. The disability community has had a challenging relationship to the animal rights community, as epitomized by continued debates involving philosophers like Peter Singer, whose works has denied personhood to certain groups of intellectually disabled individuals. But even in less extreme ways, disabled individuals and the various issues that affect us have largely been left out of the animal welfare and sustainability movements, whether because of the movements’ obsession with health and physical fitness or a lack of attention to who has access to different kinds of educational and activist events.

헤드 랜드Headlands의 접근 불가능한 공간에 앉아, 아래층에서 토론이 시작되길 기다리고 있으면서 나는 내 신체와 내 음식 선택, 두 가지 모두에 있어서 괴물처럼 느껴졌고, 나는 마이클 폴란을 비롯한 “식탁 친교table fellowship”에 대해 이야기하는 작가와 음식을 중심으로 형성할 수 있는 다양한 관계와 유대에 대해 생각했다. 폴란은 채식인의 경우 이런 유대관계가 위협받는다고 말한다. 내가 만약 다른 손님들에게 먹힌 숫송아지의 일부를 함께 먹었다면 소속감을 느꼈을까? 폴란은 자신의 채식 시도에 대해 말하길, “다른 사람들은 이제 날 배려해야 하고, 나는 이게 불편하다: 내 음식 규제가 손님과 접대하는 집주인host이라는 기본적인 관계를 파탄 낸다”. 폴란은 이제 “배려” 받아야 해서 “불편하다”고 한다. 이 경험이 새롭다는 것은 그의 특권을 노골적으로 드러낸다. 사회적 편안함에 균열을 내고 적합한 대우를 요구하는 것은 장애인이 늘 마주해야 하는 현실이다. 친구가 가고 싶어 하는 식당을 가야 하나? 계단이 있어서 내가 들려 가야 하는데? 포크를 입에 물고 혹은 포크 없이 먹어도 될까? 아니면 “동물처럼” 먹는 것을 피하고 사회적으로 용인될 수 있도록 손에 포크를 들고 먹어야 할까? 우리가 토론에 참여하도록 초대받은 이 공간이 사람들이 인지하지 못하는 특권과 장애인 차별로 점철되어 있다는 것을 지적해야 할까?

장애가 있는 많은 개인에게, 다른 이들을 불편하게 하더라도 정당한 권리를 수호하는 것은 저녁 식사 자리에서 공손한 모습을 보이는 것보다 중요하다. 폴란은 애초에 모두가 식탁까지 갈 수 있다고 전제한다. 나는 내가 이야기할 청중을 바라보고 이 식탁까지 오지 못한 존재들을 생각했다. 동물 윤리와 지속 가능성에 대한 담론에서 장애, 인종, 젠더, 혹은 소득 때문에 지워지는 존재들. 사프란 포어는 자신의 저서 “동물을 먹는다는 것에 대하여 Eating Animals”에서 간단한 질문을 던진다. “나는 사회적으로 편안한 상황을 만드는 것, 그리고 사회적 책임감을 가지고 행동하는 것을 각각 얼마만큼 중요시하는가?”

많은 면에서, 나이먼과의 대화는 여느 비건과 인도적 축산을 지지하는 사람들 간의 대화처럼 흘러갔다. 우리는 비거니즘과 지속 가능한 잡식이 환경에 미치는 영향과, 비거니즘이 정말로 “건강한” 식단인지를 논했고, 나는 오랜 시간을 들여 왜 동물이 인간으로부터 도축되지 않고 자유로운 삶을 살아 갈 권리가 있는지를 이야기했다. 나이먼과 나는 공장식 축산의 잔혹함에 대해 열성적으로 동의했고, 동물이 생각하고, 복잡한 감정을 느끼고, 능력을 가지고, 관계를 맺는 자각 능력이 있는 동물이라는 것에도 동의했다. 하지만 나이먼이 인도적으로 동물을 죽이고 먹을 수 있다는 주장을 했을 때, 나는 대부분의 경우 그렇지 않다고 말했고, 인도적 축산에 대한 정당화 논리는 종차별적일 뿐만 아니라 장애 차별적이라고 말했다.

토론 시간이 한 시간뿐이라, 나는 동물 문제와 장애의 연관성을 이야기하는 것이 불가능하다고 결정 내렸었다. 하지만 그 접근 불가능한 공간에 있으면서, 나는 이 이야기를 해야 한다고 결심했다. 내 능력이 허락하는 한, 장애와 동물 문제를 이야기해야 한다고, 내가 경험했던 배제가 고려될 수 있을지 모른다는 가능성을 위해, 내가 정치적으로 동의할 수 있는 장애의 모델을 대표해서 이야기해야 한다는 책임감을 느꼈다. 토론을 하며 나는 장애인이자 장애학 연구자로서 나의 관점이 어떻게 동물에 대한 시각에 영향을 끼치는지 설명하려고 했다. 나는 장애학이라는 분야가 어떻게 동물 윤리 담론에 중요한 질문들을 던지는지 말했다. 정상성과 자연, 가치와 효율, 상호 의존과 연약성, 그리고 권리와 자율성에 대한 이해가 이 분야에 어떻게 중요한지에 대해 설명했다. 신체적으로 자립할 수 없고, 연약하고 상호 의존해야 하는 사람들의 권리를 지키는 가장 좋은 방법은 무엇일까? 자기 자신을 지킬 수 없는 사람들, 혹은 권리의 개념을 이해하지 못한 사람들의 권리는 어떻게 지켜낼 수 있을까.

나는 자연적인 것과 정상성에 대한 제한된 해석이 어떻게 장애인과 동물에 대한 억압을 견고히 하는지 설명했다. 매년 인간의 소비를 위해 살해되는 백억의 동물 중 다수는 말 그대로 장애를 가지도록 생산된다는 것을. 가축은 좁고, 더럽고 비정상적인 환경에서 살아가기 때문에 장애를 가지게 될 뿐만 아니라, 문자 그대로 신체가 극단적으로 변하도록 폭력적으로 조작된다. 소의 젖은 소의 몸이 견딜 수 없을 정도로 많은 젖(우유)를 생산하고, 칠면조는 자기가 감당할 수 없을 정도로 큰 가슴을 가지고, 닭들은 부리가 잘려 음식을 먹기 힘들도록. 심지어 나의 질병인 관절 굽음증arthrogryposis 역시 공장식 축가에서 지나치게 잦은 빈도로 발견되어 쇠고기 잡지Beef Magazine 2008년 12월호의 주제가 되었다.

As I sat in that inaccessible space at the Headlands, waiting downstairs for the debate to begin, feeling like a freak in both my body and my food choices, I thought about Michael Pollan and the numerous other writers who speak of “table fellowship,” or the connection and bonds that can be made over food. Pollan argues that this sense of fellowship is threatened if you are a vegetarian. Would I have felt more like I belonged if I had eaten a part of the steer who was fed to the guests that night? On his attempt at being a vegetarian, Pollan writes: “Other people now have to accommodate me, and I find this uncomfortable: My new dietary restrictions throw a big wrench into the basic host-guest relationship.” Pollan feels “uncomfortable” that he now has to be “accommodated.” It is a telling privilege that this is a new experience for him. Disrupting social comfort and requesting accommodation are things disabled people confront all the time. Do we go to the restaurant our friends want to visit even though it has steps and we will have to be carried? Do we eat with a fork in our hands, versus the fork in our mouth, or no fork at all, to make ourselves more acceptable at the table — to avoid eating “like an animal”? Do we draw attention to the fact that the space we have been invited to debate it in is one of unacknowledged privilege and ableism?

For many disabled individuals, the importance of upholding a certain politeness at the dinner table is far overshadowed by something else—upholding our right to be at the dinner table, even if we make others uncomfortable. Pollan assumes you can make it to the table in the first place. I looked around at the audience I was about to speak to and thought about those who were not at the table. People whose disabilities, race, gender, or income too often render them invisible in conversations around animal ethics and sustainability. Safran Foer asks a simple question in his book “Eating Animals”: “How much do I value creating a socially comfortable situation, and how much do I value acting socially responsible?”

In many ways my debate with Niman was like many other conversations between vegans and those who support humane meat: we debated the environmental consequences of both veganism and sustainable omnivore-ism, discussed whether veganism was a “healthy” diet, and spent a long time parsing out why animals may or may not have a right to live out their lives free from slaughter by humans. Niman and I passionately agreed about the atrocities of factory farms, and we both understood animals to be sentient, thinking, feeling beings, often with complex emotions, abilities, and relationships. However, where Niman argued that it is possible to kill and eat animals compassionately, I argued that in almost all cases it is not and that the justifications for such positions are not only speciesist but ableist.

As the debate was only an hour, I had previously decided that trying to talk about disability as it relates to animal issues would not be possible. But after being in that inaccessible space, I felt compelled to discuss it. I felt a responsibility to represent disability and animal issues to the best of my ability — to represent a model of disability I politically agreed with in hopes that some of the marginalization I had experienced would be considered. Throughout the debate, I tried to explain how my perspective as a disabled person and as a disability scholar influenced my views on animals. I spoke about how the field of disability studies raises questions that are important to the animal-ethics discussion. Questions about normalcy and nature, value and efficiency, interdependence and vulnerability, as well as more specific concerns about rights and autonomy, are central to the field. What is the best way to protect the rights of those who may not be physically autonomous but are vulnerable and interdependent? How can the

rights of those who cannot protect their own, or those who cannot understand the concept of a right, be protected?

I described how limited interpretations of what is natural and normal leads to the continued oppression of both disabled people and animals. Of the tens of billions of animals killed every year for human use, many are literally manufactured to be disabled. Industrialized farm animals not only live in such cramped, filthy, and unnatural conditions that disabilities become common but also are literally bred and violently altered to physically damaging extremes, where udders produce too much milk for a cow’s body to hold, where turkeys cannot bear the weight of their own giant breasts, and where chickens are left with amputated beaks that make it difficult for them to eat. Even my own disability, arthrogryposis, is found often enough on factory farms to have been the subject of Beef Magazine’s December 2008 issue.

나는 어떻게 동물이 장애 차별적인 인간 특성과 능력을 기준으로 판단 당하는지도 이야기했다. 무능력하고 부족하며 다르다는 이유로, 어떻게 동물이 장애인과 같은 이유로 열등하고 소중하지 않은 존재들로 여겨지는지. 비장애인 신체에 특권을 부여하는 이 사회에 의해 동물의 몸은 비장애인의 몸과 끊임없이 비교되고, 이는 우리가 동물에게 가하는 잔혹함을 정당화는 근거가 된다. 장애인 차별이 정당화하고 특권을 부여하는 “정상” 신체는 비-장애non-disabled일 뿐만 아니라 비-동물non-animal이다.

마지막으로 나는 장애학에 대해 나눌 수 있는 내용을 나누려고 했다. 장애학은 신체와 지적 능력에 국한되지 않고 인간 삶의 가치를 찾을 수 있는 다양한 방법을 제시한다는 것. 장애학 학자들은 우리에게 가치와 존엄성을 주는 것이 우리의 지능, 합리성, 민첩성, 신체적 자립, 혹은 직립 보행이 아니라고 한다. 우리는 삶이란, 당신이 다운 증후군이 있는 사람이든, 뇌성마비가 있는 사람이든, 사지 마비가 있는 사람이든, 자폐증이 있는 사람이든, 혹은 나처럼 관절 굽음증이 있는 사람이든, 살아갈 가치가 있다고 여겨져야 한다고 말한다. 만약 장애인권을 이야기하는 사람들이, 장애가 있는; 합리성이나 신체적 자립과 같이 사회가 중요시하는 능력이 떨어지는 사람들의 권리의 보장을 주장할 때, 이러한 주장이 비인간 동물에게 미치는 영향이 무엇일까?

토론이 끝나고, 나는 패배감이 엄습하는 것을 느꼈다. 동물권에 대해서가 아니라 장애인권에 대해서. 나는 내가 대표한 장애 정치가 잘못 이해될 것이라고, 사람들은 인간 동물이자 비장애인인 자신의 특권을 곱씹어보기보다 내가 내 장애를 이용해 동물권을 옹호한다고 생각할 것으로 생각했다. 나를 향해 말을 한 첫 사람은 지적 장애가 있는 아이의 어머니로 자신을 소개했다. 그는 한 편으로는 나에게 감명받은 듯했고 (나를 장애 극복 서사를 가진 슈퍼 장애인으로 보는듯) 다른 한편으로는 나를 구해주려고 하는 것처럼 보였다. “이건 당신의 명분에 도움이 안 돼요,” 그는 반복적으로 말했다, “자신을 동물과 비유하지 않아도 돼요.” 어떤 면에서는 이 여성이 왜 이렇게 말했는지 이해했다. 지적 장애가 있는 개인들은 싱어와 같은 부류의 동물권론자들이 내세우는 담론으로부터 좋은 대접을 받지 못했다. 철학자 리시아 칼슨Licia Carlson이 말하듯이 “우리가 이 개념의 악용을 진지하게 고려하고, 현재 철학에서 지적 장애의 배제에 대해 생각한다면, 이 담론에서 ‘지적 장애인’에게 배정된 역할에 대해 비판적으로 재고해야 한다.” 나는 내가 나를 비인간 동물에 빗댄 것이 아니라 우리가 겪는 공통된 억압을 비교한 것이라고 말했다. 장애인과 비인간 동물은, 비슷한 억압을 경험한다. 물론 우리는 결국 모두 동물이기에, 내가 나를 동물에 비유하는 것이 꼭 부정적인 것은 아니지만 말이다. 그는 자신의 아이를 동물의 상황에 비유하고 싶지 않다고 말했고, 그 둘은 무관하다고 했다. 자신의 아이는 동물이 아니며, 내가 만든 이 연결고리는 나와 나를 포함한 다른 이들에게 부당하다고 말했다. 그는 나에게 화가 난 것은 아니었지만 만약 내가 비장애인이었을 경우 화를 냈을 것이다. 오히려 그는 나를 위해 슬퍼하는 것처럼 보였다. 마치 내가 장애 자긍심과 자신감이 떨어져서, 나를 동물 이상으로 생각하지 못한다는 듯이.

I also spoke about how animals are continually judged by ableist human traits and abilities. How we understand animals as inferior and not valuable for many of the same reasons disabled people have viewed these ways — they are seen as incapable, as lacking, and as different. Animals are clearly affected by the privileging of the able-bodied human ideal, which is constantly put up as the standard against which they are judged, justifying the cruelty we so often inflict on them. The abled body that ableism perpetuates and privileges are always not only non-disabled but also non-animal.

In the end, I tried to share what I could about disability studies, how it offers new ways of valuing human life that is not limited by specific physical or mental capabilities. Disability studies scholars argue that it is not specifically our intelligence, our rationality, our ability, our physical independence, or our bipedal posture that gives us dignity and value. We argue that life is, and should be presumed to be, worth living, whether you are a person with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, quadriplegia, autism, or like me, arthrogryposis. But, I asked, if disability advocates argue for the protection of the rights of those of us who are disabled, those of us who are lacking certain highly valued abilities like rationality and physical independence, then what are the consequences of these arguments in regard to nonhuman animals?

As the debate ended, I felt a sense of defeat creep over me — not over animal issues but over disability issues. I had a strong feeling that the disability politics I had represented would be misunderstood: instead of people considering their own privilege as human and nondisabled, I would be seen as using my disability to boost animal issues. The very first person who came up to speak to me introduced herself as the mother of an intellectually disabled child. She was both impressed with me (in a sort of supercrip way) and worried about me—like someone trying to save my soul. “This doesn’t help your cause.” She kept saying, “You don’t have to compare yourself to an animal.” In some ways, I understood where the woman was coming from. Individuals with intellectual disabilities have not been treated well by the branch of animal rights discourse promoted by people like Singer. As the philosopher, Licia Carlson writes, “If we take seriously the potential for conceptual exploitation and the current marginalization of intellectual disability in philosophy, we must critically consider the roles that the “intellectually disabled” has been assigned to play in this discourse.” I tried to explain that I was not really meaning to compare myself to an animal, but was rather comparing our shared oppressions. Disabled people and nonhuman animals, I told her, are often oppressed by similar forces. I told her, though, that to me being compared to an animal does not have to be negative — after all, we are all animals. She told me she did not want to compare her disabled child’s situation to an animal’s situation, that they were not related. Her child was not an animal. I was doing a disservice to myself and others by making these connections. The woman never got mad at me, as I assume she would have an able-bodied person saying what I was saying. Instead, she seemed sad for me, as if I lacked the disability pride and confidence to think of myself as anything more than animal.

만약 내가 사회적 예의범절에 따라 다른 사람들을 편안함을 고려하지 않고, 적합한 공간을 제공하도록 요구했다면 장애가 있는 인간으로서 나의 자존심이 다르게 비쳤을까? 만약 내가, 행사장에 접근할 나의 권리를 주장하며 행사장에 왔다면, 내 신체에 대한 나의 자존감이 만천하에 드러나서, 동물과 나의 관계에 대한 설명도 내 장애에 대한 나의 사랑의 표현으로 받아들여졌을까? 나의 행동은 행사 진행을 방해하고, 다른 이들을 불편하게 했겠지만 나는 정당한 공간을 요구함으로써 다른 식탁 친교의 풍경을 주장했을 것이다. 그 공간의 접근 불가능성은 그날 나의 언어를 조각했고, 따라서 내가 동물과 장애에 대한 억압이 자연스러운 것으로 치부되어 지워지는 다양한 모습에 초점을 맞추게 했다. 사람들이 저녁으로 숫송아지를 먹는 동안 장애가 있는 사람은 아래층에서 기다리는 이 모습에. 이만 여기까지 입니다!

(제 생각에 제 책에 실린 이 부분의 전체적인 주장은 비거니즘이 장애라는 게 아닙니다, 제가 말하고 하자는 것은 그게 아니라 비거니즘이 괴상하게 묘사된다는 것이에요. 간단하게 말하자면, 비건인 사람들은 미디어에서 괴짜로 표현된다는 거죠. 다시 강조하자면, 저는 마이클 폴란이나 나이먼 같은 사람에 관해 쓸 때는 주류 담론에 대해 이야기하고 있어요, 정말 폭넓은 일반 대중을 대상으로 글을 쓰는 사람들이요. 이게 저의 주장을 더 명확하게 해주는지는 모르겠어요. 이 글 또한 마찬가지로요. 저는 제가 겪는 접근성과 장애 문제에 관한 경험이 제가 그날 이야기 하도록 초청받은 행사의 주제인 동물 윤리와 교차하는 지점에 대해 이야기하기 위해 제 개인적인 경험을 빌리려고 한 것입니다. 이 글 자체는 왜 제가 동물 윤리와 장애인권운동이 연관되어 있다고 생각하는지 사람들에게 그다지 와 닿지 않은 것 같아요. 그보다는 식탁 친교와 접근성을 이야기하는 특정 담론들을 다루는 이야기에 가까워요.

If I had demanded accommodation, instead of politely following social etiquette and making others feel comfortable, would my confidence as a disabled human being have come through differently? I wonder whether, if I had arrived at the event insisting on my body’s right to access, would the confidence I have in my embodiment have been so unmistakable that even discussing my relationship to animals would have been recognized as a gesture of my love for disability? Perhaps my behaviour would have been seen as disruptive, perhaps it would have made others uncomfortable, but by demanding accommodation I would have insisted on a different kind of table fellowship. The inaccessibility of the space framed my words that night and led me to focus on the ways in which animal oppression and disability oppression are made invisible by being rendered as simply natural: steers are served for dinner and disabled people wait downstairs. That’s what I got for y’all.

(I think my larger argument in this particular section of my book was really not that veganism is a disability, that’s not what I’m arguing, I am arguing that veganism is freaked. That basically people who are vegans are represented as freaks in the media. Again, I am dealing with much more mainstream discourse in terms of writing about people like Michael Pollan and Nyman, these people who are writing for really broad, general audiences. I don’t know whether that helps clarify what I was arguing about. This piece also, I was trying to use a personal example of dealing with access and disability issues and the ways in which I felt like those issues intersected with the stuff that I was actually invited to talk about which was animal ethics. In this particular piece, I didn’t really get into too much the heart of why I think disability studies or disability activism and animal ethics are connected, it was more a narrative dealing with the more nuanced particular conversations about table fellowship and access.)

자막 기능이있는 전체 비디오는 여기에서 볼 수 있습니다

Full video with closed captioning available here

Sunaura Taylor는 예술가, 작가, 활동가입니다. 테일러의 작품은 큐 아트 재단 (CUE Art Foundation), 스미소니언 박물관 (The Smithsonian Institution), 버클리 미술 박물관 (Berkeley Art Museum) 등 전국 각지에서 전시되었습니다. 그녀는 Joan Mitchell 재단 MFA 보조금 및 동물 및 문화 보조금을 비롯한 수많은 상을 수상했습니다. 각 작품은 월간 리뷰, 예!와 같이 다양한 편집 된 콜렉션 및 출판물에 인쇄되었습니다. 잡지, American Quarterly 및 Qui Parle. Taylor는 Astra Taylor의 Film * Examined Life * (Zeitgeist 2008)에서 철학자 Judith Butler와 함께 작업했습니다. Taylor는 University of California, Berkeley에서 미술학 석사 학위를 취득했습니다. 페미니스트 프레스 (Feminist Press)에서 동물 윤리와 장애 연구의 교차점을 탐구하는 그녀의 저서 “부담의 짐승들 (Beasts of Burden)”이 나옵니다. 그녀는 현재 Ph.D. 뉴욕시 사회 문화 분석학과 미국학과 학생.

Sunaura Taylor is an artist, writer, and activist. Taylor’s artworks have been exhibited at venues across the country, including the CUE Art Foundation, the Smithsonian Institution and the Berkeley Art Museum. She is the recipient of numerous awards including a Joan Mitchell Foundation MFA Grant and an Animals and Culture Grant. Her written work has been printed in various edited collections as well as in publications such as the Monthly Review, Yes! Magazine, American Quarterly and Qui Parle. Taylor worked with philosopher Judith Butler on Astra Taylor’s film *Examined Life*(Zeitgeist 2008). Taylor holds an MFA in art practice from the University of California, Berkeley. Her book *Beasts of Burden,* which explores the intersections of animal ethics and disability studies, is forthcoming from the Feminist Press. She is currently a PhD student in American Studies in the Department of Social and Cultural Analysis at NYU.

Leave a comment