*this is a written transcript of a video presentation available here with Closed Captioning*

hi my name is archie.

and this is Phoebe.

thanks for tuning in to my presentation.

so to briefly summarize what i am going to be talking about today – basically, this is a presentation about mental health, mental illness, about identities of madness and how those topics interrelate with animal advocacy, animal defence, animal rights.

first, to start off, i’m going to offer up a land acknowledgement i am a white settler residing on stolen indigenous territory and i continue to benefit from a lot of the privileges that come from the result of historic and ongoing colonization of Turtle Island, here. specifically, i am on Saanich (WSANEC), Lekwungen (Songhees) and Esquimalt – Coast Salish and Straits Salish Nations.

if you can, i would really encourage you to just pause the video right now and make sure that you are at least familiar with the people’s territory that you are residing on, potentially occupying, depending on where you’re watching this from.

those conversations are very important. i think they’re necessary for another video altogether, but i think that’s important to acknowledge.

and to go further, i’m going to just also be honest in saying that a lot of the material content i’m going to be talking about in this video – a lot of it comes from the lived experiences and from the mental-emotional labour of other peoples.

so i’m not when i am presenting this, material i’m not looking for credit or validation as something that i produced.

i’m really just trying to make this space, this conference here, using my privilege to access it, to bring up these kinds of conversations that are really important when we’re talking about disability, about animal politics.

as well, i want to offer a content warning for what I’m going to be talking about it’s a lot of potentially triggering material. it’s going to be conversations about ableism, about specifically mental illness, about disability. there is going to be conversations about speciesism, about animal abuse and animal testing. there’s going to be conversations about misogyny, about patriarchy, a lot of gaslighting, and medicalization of women, and womyns’ bodies.

finally, for the introduction, i just want to do a breathe to ground ourselves as we go through this presentation. i think it’s really important, depending if this is the first video you are watching on its own, or if you are going to be watching this video as part of the wider conference that this is happening with. i think it’s really important that you’re really present with what i’m going to be talking about, so that way your mind is here and you’re not still processing a lot of the other information that you may have picked up throughout the day, depending on where you’re coming from. if we can just do one quick breath, i would appreciate that. just a slow breath in… and a slow breath out…

okay – thank you.

to start, when i say “embracing our herstory of animal loving madness”, what i am talking about? to explain that, i think it’d be best if i go back through the title itself.

“animal loving madness” – this was once considered a legitimate mental disorder among the medical industry. they characterized it as a dangerous, obsessive insanity among people who were over-concerned, over-empathetic with the suffering of animals.

the term “zoophil-psychosis” was the clinical term developed and it literally means “psychotic love of animals”. it was first coined by Charles Dana in 1909. Dana was a very influential neurologist in the United States, at Cornell, and a leading animal vivisectionist. he did a lot of animal testing, he was very invested in the industry of animal testing. Dana pronounced this medical disorder, of zoophil-psychosis, calling it a dangerous psychological malady that was manifesting in people who were advocating for animals.

Dana first published this again in 1909, in The Medical Record, which was a scientific journal. he described the characteristics through case studies saying that it was enduring sensitivity, an excessive over-concern with animals. some of the cases he talked about were people who were very bothered by horses being mistreated in the streets – this is the 1900s when horse carriages were very common. people who were getting upset by the beatings of horses, he characterized this as suffering from zoophil-psychosis. as well, people trying to intake a lot of stray cats, cats needing homes, cat fostering. he found this again to be a sort of bizarre obsession that was psychologically dangerous, and he was treating this medically.

what Dana was getting at here, again just because he was very invested in animal testing, from his position, his status, he was describing that people who were getting sick with this animal empathy, that it was a danger to civilized society, a danger to scientific progress, that it was just a danger to people manifesting psychopathic characteristics which were initially being understood as animal advocacy, as animal rights. whereas he was trying to instead say that it’s not a political issue, it’s actually a group of people with mental illness who need to be treated.

and it’s really convenient that his diagnosis created a massive stigma around his opponents who were trying to undermine his scientific research, his economic investments, and what he was doing. at the time, in the early 1900s, in the united states, anti-vivisection was gaining a lot of traction, it was gaining a lot of popularity and political clout in society. a lot of the campaigns were being led by women who were also involved in a lot of suffragette movements and a lot of child protection, advocacy for the poor and homeless. so with this clinical diagnosis developed, Dana and the other medical industry, along with the media, were able to really redirect what the conversations were about. instead of about testing on animals – the legitimacy and morality of that – it was conversations about the mental well-being of people challenging these doctors, these men in offices.

a lot of mainstream media picked up on this. New York Times especially was very supportive of this diagnosis. there was a lot of articles, some of them included titles “Passion for Animals Really a Disease”, with a lot of really ridiculous quotes saying that “anti-vivisectionists care little for human suffering” and that there was a “preposterous love of pet animals that push people to the verge of insanity”. another editorial in the New York Times, in 1910, saying that anti-vivisectionists, “they are a queer people involving an actual hatred of human beings”. again, this is the kind of content that is being put out by the media in defence of Charles Dana and this zoophil-psychosis diagnosis.

so with the “herstory of animal madness”, this is applying a feminist perspective towards understanding what this diagnosis of zoophil-psychosis was really all about. when you dive deeper you can understand that Dana and the wider medical establishment, as well as the media, were also gendering this diagnosis of mental illness. they were characterizing it to be particularly common among women. among women who were out in the streets, politically aggressive in opposing dominant institutions like the medical industry. they were describing zoophil-psychosis as leading to symptoms where people would abandon their domestic responsibilities.

essentially reading through those lines, what the doctors were saying is that these women were not being responsible according to their standards of what a woman should be doing. they wanted to medicalize that as a dangerous psychosis. and there was a lot of quotes, even directly from Charles Danas’ articles describing that zoophil-psychosis could lead to secondary symptoms including “asexuality, selfishness, jealousy, foolishness, and other related disinterest”, that would relate to “caring more for felines than being a nurturing wife and potential mother”. as well, the Medical Record, again this popular scientific journal, describing in a 1910 article saying that “victims of this zoophil-psychosis consisted of women who coddle their pets and love them more than babies”.

this zoophil-psychosis was really related to the diagnosis of hysteria, as a psychological disorder among women.

hysterical neurosis was not removed from the DSM until 1980, so it was a very popular way to undermine the voices of women by describing their anger, any resentment, any defiance towards patriarchal institutions as being a form of mental disturbance that needs to be treated instead of actually listened to. with this, you can understand that when there is a male-dominated institution, in 1909, of the medical industry, of the media – again there were more articles coming out with titles saying “Women who love Animals Hate People”.

again just really blatant examples that, by manufacturing this illness they were able to also simultaneously uphold repressive gender roles by dismissing the women who were leading campaigns against the testing of animals.

okay, talking about “embracing the animal-loving madness”. what i am talking about here is trying to develop more comprehensive ways of having radical disability politics into animal advocacy, animal defence, specifically around mental illness. when i am talking about zoophil-psychosis earlier, i am not meaning to somehow suggest that it is somehow an origin of ableism in animal rights mainstream culture today, but more that it is an interesting illustrative example of an overlap between disability and animal advocacy back a century ago.

but currently, mainstream animal rights culture is definitely lacking in considering disability within a radical empowering way, of building any significant ties with communities with disabilities. there is a lot of examples that you can draw from. just briefly to go over, you have a lot of the major organizations, the major thinkers, who take up a lot of space and gather a lot of attention and status.

just briefly to go over, you have a lot of the major organizations, the major thinkers, who take up a lot of space and gather a lot of attention and status.

you know there, is PeTA with a lot of their campaigns talking about body-shaming, and offering “healthy solutions” towards fixing people’s physical illnesses or preventing mental illnesses, in the case of autism in one of their autism anti-dairy campaign posters.

as well, there are popular writers like Peter Singer who talk about elevating animals with higher IQ over peoples with disabilities who have lower IQs. then there is a lot of language around equating animal abuse with mental illness – that’s one of the most popular things that i found. there is Gary Francione who talks frequently about “moral schizophrenia”, and there is just a lot of language thrown around, where it’s equating meat-eating with sick people, with animal abuse as psychopaths, and a lot of slogans brought up such as “people being blind to justice”, or “standing up for animals”, and “being the voice for the voiceless”.

just talking about really ableist language as an effort to validate what this animal rights politics is about. i found a lot of this to be shortcuts to really articulating well what we are talking about when we’re saying that there is speciesism in our societies that exploit animal bodies. but referring to ableist rhetoric that is built on the oppression of other bodies, other minds, peoples with disabilities that this is doomed to failure, doomed to breaking ties instead of actually building solidarity within communities.

i think what is a really important way of moving past these sorts of things, about developing a more empowering sense of madness, about mad pride within animal rights, in animal liberation. i think the ways of doing this are moving away from a lot of the emphasis on presenting animal politics as rational, as scientific, as objective. i understand the reasons for that, as a way to cater towards mainstream society and a lot of the politically influential institutions and people.

but i think in the process of doing this we are losing a really important element that our emotions, that our empathy is really powerful, radical tools. they’re radical expressions of who we are as people, as animals. i don’t think that those are things that we should be negotiating with, or apologizing for. there is a lot of really great quotes i can draw from, from books i’ve read about these sorts of things.

where pattrice jones, in the book “Aftershock”, which is about activist trauma so it’s a really interesting read if you have the time and money to devote towards that, but one of the few sentences that i drew upon for this presentation is where pattrice is describing how “men of many cultures have sought to transcend to their own bodies while reducing women and animals to their body parts. seeing themselves as more rationale and self-determined, men claim the right to rule over those they see as more emotional, impulsive and bound to bodily rhythms.” i think that is really a succinct way of describing what our society, built on speciesism, on ableism, is really nurturing things of objectivity, of disconnection from our bodies, from our minds, and a lot of fear of disability, of illness. i think those are things that are actually empowering for radical liberation, and things that we should not shy away from.

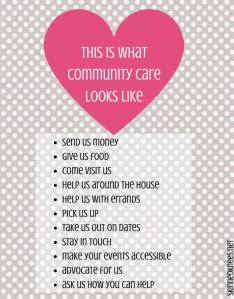

ways we can keep going with that, with empowering animal madness, of almost trying to reclaim identities of zoophil-psychosis. i think there needs to be a lot more emphasis on community care when we are doing animal advocacy.

this can look like a lot of different ways, but the basic idea here is that we’re not treating self-care on its own sake, but especially for peoples with illnesses, chronic illnesses, and disabilities – not treating that as somehow a side issue, as an afterthought, that is not associated with organizing, with protests, with activism. because that is a very community-involved process, where we can make space and give up space for people who need to be heard when their needs are such that they need more attention and more community support. i think that when we do this, we can move away from perceiving dependency, interdependency and vulnerability as negative things. i think those are things that we have been taught to be afraid of, out of weakness, fear of being seeing as weak, but i think they are actually very powerful revolutionary things to really explore more.

when we’re doing this, when we’re talking about activism for animals, i think we can for ourselves take a step back and really look out “what is activism?” and “who is defining what activism is?”.

so instead of the very common depictions of activists as the people marching in the streets, making a lot of noise and taking up a lot of space, while it is important, i think it is also important to acknowledge that people who are taking time off to care for themselves, with an illness, i think that is activism in its own right. people, single mothers, who are raising children but can’t attend group meetings, can’t attend potlucks, because they are working or because they have disabilities and live in a community that is architecturally designed to not accommodate them, prevents them from attending things, protests and other social gatherings. i think we need to respect that those are forms of activism to exist in societies that are not built to support those kinds of people. supporting those marginalized peoples, that is activism in its own right.

so yeah, i think that’s really important, that we figure out ways to redefine what our boundaries are, of activism, of community support, of self-care, of what liberation is as a whole. understand that disability, mental illness, these aren’t things that need to be perceived as something to be fixed, as though there’s something wrong with a disability, as though it’s not wholly natural as “health” as we know it. i think the idea here is that we need to be making space for communities and peoples with disabilities to be able to access these kinds of conversations right here, and these sorts of issues towards liberation.

finally, i think another really important way that we can move towards making more accessible animal politics happen in our communities for people with physical disabilities and for mental illnesses here, i think depending on what the community actions are, whether it’s the more confrontational protests in the streets involving police, or if it’s engaging with animals who are being exploited right in front of us in such cases as slaughterhouses, or zoos, marine parks, things like that, i think it’s really ideal if we can try to develop more of an infrastructure for support of people who are coming out to these things, to have some way to debrief, ideally with people who are trained with post-traumatic stress disorder to help transition people to not take a lot of this grief, a lot of this really violent speciesism and other things that we can experience at protests, to not take all that home with us alone. again, what i was saying earlier about making self-care and self-love for people with illnesses and disabilities, making that a community affair. i think the emphasis on protesting should really be only half of the event as a whole, whereas the other half should be meant towards really feeding the community afterwards so that we can leave that space and feel that we have support and that we are taking care of by ourselves and by each other. i think that those sorts of steps are going to make a more sustainable, a more radical space available for long-term success in liberation, and more examples of momentary liberation for people to feel good and feel like we are doing things that are really feeding our souls and our spirits for resisting oppression.

i think it’s important for us to remember that taking zoophil-psychosis as a case study example to illustrate overlap between disability and animal politics, that there are a lot of ableism logic that has been internalized and kept along through the years in animal rights culture. i think there is absolutely so much potential for us to drop all of those habits and those sorts of relationships of supporting other oppressive dynamics – we can drop that from a lot of our community organizing and that we can move towards a lot more empowering ways of negotiating space, of connecting with different communities and of challenging the status quo. i think that doing that by embracing more of our emotions, embracing more of our empathy, and not being afraid of madness, of taking pride in our mad identities and our mental illnesses, i think there is really great potential that we can shift our perspectives in how we understand what health is, and what disability is, and what liberation is going to look like, today, tomorrow and for the future.

yeah, that is everything. thanks for listening.

okay bye.

Further Readings

- Leaving Evidence – disability justice writer and organizer Mia Mingus, a queer physically-disabled woman of colour, writing about understanding how ableism is interconnected with racism, colonialism, capitalism and cis-gendered heteropatriarchy

- For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States, by Diane L. Beers, Ohio University Press, May 25, 2006.

- Zoophilpsychosis: Why Animals are What’s Wrong with Sentimentality. Menely, Tobias. 2007. Published by University of Nebraska Press. Vol 15, No 1-2. Pp 244-267.

- Antivivisection and the Charge of Zoophil-Psychosis in the Early Twentieth Century. Craig Buettinger: published in The Historian, Vol. 55, 1993, pp. 277-288

- Women and Antivivisection in Late Nineteenth-Century America. Craig Buettinger, published in Oxford University Press, Journal of Social History, Vol 30, No 4, 1997, pp 857-872.

- The Mad Pride: A Celebration of Mad Culture, Robert Dellar, Esther Leslie, Ben Watson. Published by Spare Change Books (2003)

- The Icarus Project – a support network and media project by and for people who experience the world in ways that are often diagnosed as mental illness, advancing social justice by fostering mutual aid practices that reconnect healing and collective liberation.

- Overcoming the Language of Oppression: Promoting Cultural Change with Words by Pat Risser, presented at the 2008 Annual Clinical Forum on Mental Health: Turning Knowledge into Practice. North Dakota Department of Human Services.

- Mentalism, disability rights and modern eugenics in a ‘brave new world‘. 2009. Diane Wiener, Rebecca Ribeiro and Kurt Warner. Disability & Society. Volume 24, Issue 5,

- The Madwoman in the Academy, or, Revealing the Invisible Straightjacket: Theorizing and Teaching Saneism and Sane Privilege. Vol 33, No 1, Wolframe.

archie identifies as a chronically ill, cis-queer, anarchist zen vegan. they write visionary fiction about animal & earth liberation while also managing the online resource called ELK (www.humanrightsareanimalrights.com), which has organized large-scale events around intersectionality, anti-patriarchy and anti-pipeline resistance. with a master’s degree in criminology, archie has written & led conversations around anti-speciesism, prison abolitionism – and the collusion of privileged mainstream animal rights with other oppressions. as a white settler currently residing on the territories of WSANEC (Saanich), Lekwungen (Songhees) & Esquimalt People’s of the Coast Salish and Straits Salish Nations, archie lives with one human, a boxer, a beagle and a kitty.